|

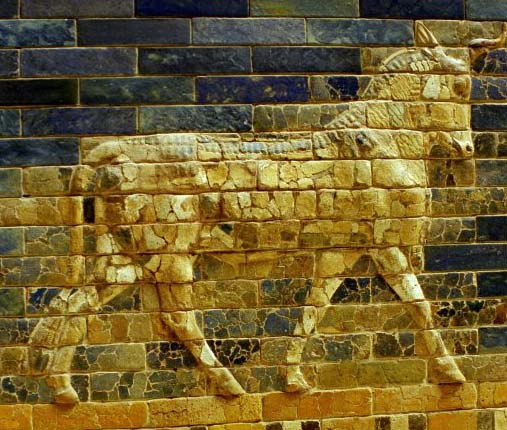

Water can symbolize the human heart and its emotions, of course; the flow of earthly feelings. But it can also be used to symbolize something of a much higher level in the order of creation: something from beyond the range of thoughts and feelings; something from the realm of spirit. This perhaps is the level of holy water, of baptism, and all manner of religious rites involving water. Just as life itself depends on the presence of water, so water can symbolize the power of life. A Sacred RiverIt is not always desirable to use the symbols or images of one or another religion to symbolize the river of life, the spiritual cataract—the fish-ladder of souls that really does exist on the inner plane. To do so would be to invite invidious comparisons with other religions and ways. As you will have noticed, very religious people tend to suppose —to believe—that their own religion comprises spiritual reality in fact, rather than merely a symbol of that reality, and it is always best not to argue with extreme points of view. It is far safer to use religious ideas from long ago to help explain the principle of "sacred river", using symbols from a religion that nobody follows anymore. This is why I shall take the Euphrates of the ancient Babylonians as my "sacred river".Now, Babylon has acquired a very bad name over the millennia which have elapsed since its heyday, mainly because of the indignation caused by the capture and exile of Israel at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar, and the detention in Babylon of skilled Israeli workers and intellectuals as virtual slaves of the Babylonians. Babylon thereafter was given a very "bad press". But their symbols of spirituality were instinctively sound, though overlaid with what may seem to us the childlike superstitions of their day. Every trace of the ancient cities may have disappeared, but hard-baked clay lasts, and thousands of cuneiform clay tablets have been unearthed by archeologists, especially from beneath what must have been the city records office and public library of their day. Most of what is known of the city-state of Babylon came from the information on these tablets. They tell, for instance, of a great annual ceremony involving King Nebuchadnezzar and his priests during which they followed and re-enacted their own symbolic spiritual ascent known to them as "the sacred path of Marduk." The Babylonians were probably the first among men to isolate and describe traits of the human psychology, and they related these to the known planets, forming the basis of present-day astrology. They personified these planets, complete with their human traits, as gods and goddesses, but they went a step further than that: in the ethos of "as above, so below", the land they lived in was also made to reflect this system on another scale. The very name "Babylon" has come to imply an excess of materiality, wealth and luxury, and shameless idolatry, and indeed it was very likely the wealthiest city-state of its time. The name comes from the phrase "gateway of God", and much of Babylonian history justifies this title. The gateway, a means of passing through to a different spiritual condition, has to function by way of the soul. This I suppose is self-evident, though many may gloss over it. It is patently true that the concept of "God" will include materiality as well as spirituality, but only spirit can activate spirit, or approach matters of spirit; and spirit within the human sphere has to function by way of the soul, by activating the soul— the soul that may well have lain dormant for many years. "Spirit" must not be confused with emotion. Spirit is not to be known by science, not to be discovered by clever minds. Nebuchadnezzar and his priestly hierarchy may not have been clever by our modern standards. They would probably seem to us as thick as the proverbial two short planks. Neither were they saintly people—far from it. But they were aware of an all-important principle: that soul represents the way to a higher state, and that soul must be allowed to lead. It cannot be bypassed. Babylon itself was the city-state which ruled the land of Mesopotamia, the area between the two major rivers of the Tigris and the Euphrates, and equating to modern Iraq. The civic motto of the city was "Marduk is Bel"—the soul is lord. Their city name, "Gateway of God", takes the matter a stage further, for if Babylon represented the soul, the other sister cities of the Mesopotamian plain each represented another, essential but less exalted, part of the of the human organism. These different "rulers" of the human condition were symbolized by idols—given solidity of form—perhaps so that the uneducated masses might have some inkling of the principles involved. That seemingly simple fact caused moral outrage and righteous indignation in people who happened to use a different set of symbols: people who thought that their religious symbols were the only true symbols, or even that their religious symbols were not symbols at all, but spiritual reality itself. Babylon then, "city of a thousand idols", was in fact the city of the soul, setting the principle of the inner self above that of the outward personality. For kings and councillors, for government officials, the highest recognized authority was symbolized by Shamash, the sun—the spirit of openness and justice whose light shines on all, who exposes misdeeds and uncovers evil, the champion of triumphal careers, patron of all outward accomplishments of the rich and famous. Worldly success, for Babylonians, belonged to Shamash. But spiritual progress belonged to Marduk. Shamash ruled over the outer self; Marduk, perhaps better known to us as Jupiter, ruled over the inner self. Whilst Babylon itself honoured Marduk, the other cities of Mesopotamia each honoured their own patron deity, symbolized by their idols. The city of Borsippa, ten miles away to the south-west on the banks of the Euphrates, was the home ground of Nabo or Nebu (the one we know as Mercury)—representative of thoughts, the intellectual centre. A similar distance away to the north-east, the city of Cuthah honoured the warlike Nergal (known to us as Mars)—seat of passions, the dreaded one who takes command of the underworld (for this is certainly where the passions ultimately lead). For this reason the city of Cuthah was known throughout the region as the "assembly-place of ghosts". It was also the martial centre for the region, the fortress-town of Nebuchadnezzar's crack troops. The patron god of Lagash, many miles away on the edge of the Sumerian salt marshes, was Ninurta (known to us as Saturn). This was a desolate place associated in the Babylonians' minds with death and dissolution. The great goddess Ishtar (known to us as Venus), seat of emotions, was particularly venerated in the city of Erech, again far to the south. The Euphrates had changed its course at least a thousand years before the advent of Nebuchadnezzar II, and Erech stood near the banks of the original mainstream course, now reduced to a trickle by comparison. It was a symbol, perhaps, of lost glory: Erech had been one of the most powerful of ancient city-states, even before the emergence of Babylonia itself. The heart, you could say, will sooner or later be obliged to take second place to soul. In fact all the outlying cities, towns and villages of the Mesopotamian plain were, or over the years gradually became, symbols of the limbs and extremities and functions of a parent body, and this parent body of the first millennium BC was Babylon. Marduk was always considered chief among these far-flung deities, no matter how much more terrible earthwards, or even how much more exalted heavenwards they may have seemed as individual powers. Though the other gods and goddesses can be thought of as having a particular role to play, Marduk himself was not and nor could he be limited to any particular set of rules. The reason for this is very plain: the human soul represents wholeness; it contains within itself all human possibilities, and cannot correctly be thought of as isolated or limited in any way, or as representing this or that quality. Do not make the common mistake of assuming "soul" to be confined to holy or spiritual or even religious matters. Marduk, as a ponderable symbol of the soul, contained every known characteristic within his own nature. This was and still is the actual nature of soul: simultaneously the nucleus and the circumference of the self, both impetus and boundary of all human actions. Even though we are not normally aware of it, it is only by way of soul that consciousness can reach and quicken our coarse, material parts, our sensations, emotions and thoughts. And do not make the even bigger mistake of confusing the personal soul with the Holy Spirit. Spirit is impersonal; soul is personal. But it is only by way of one's own soul that genuine spirituality can be contacted, that our own spiritual status can be improved, and the world of heavenly beings approached. The Sacred Path of MardukLet us be onlookers at this great annual festival, for the onlookers were also thereby the participators. As we assemble, the ceremony will already have begun in secret, as they put it: "invisible, beyond human sight", and known only to the Babylonian priesthood: this was when the idol of Marduk (representing the human soul) was ceremoniously immersed in the Euphrates—symbolically, that is, introduced to spirit and thus brought to life. Only after this initial ceremony of symbolically uniting soul and spirit had been carried out, could the public procession taken place.From the banks of the great Euphrates, the procession moved off with a roll of drums and a mighty clash of cymbals, a braying of horns and trumpets. Then to the more melodious accompaniment of harps and lyres, the temple choir struck up the processional anthem of praise to the quickened Marduk. At the head of the procession walked the high priest, striking in his black and white robes, embroidered with gold. On his ornate headdress, worked in scarlet, was the winged lion symbol of protection from evil. Next to the priest walked his acolyte, a young boy nearing puberty, clad all in green, carrying head-high a silver bowl of holy water, freshly drawn from the Euphrates and newly blessed. Into this bowl the priest dipped a bundle of tamarisk twigs bearing leaves and flowers, and with it he sprinkled holy water left and right, from time to time arching it high in the air so that it fell as drops over the priests and dignitaries walking behind. Immediately behind the high priest walked two ranks of lesser priests, impressive in their robes of red and black, bearing on their shoulders a woven-rush litter which swayed lightly to the rhythm of their steps. Upon the litter sat the statue, the idol of Marduk, carved out of scented cedar wood and encased in gleaming bronze, inlaid with patterns of gold, silver, and the pure blue of lapis lazuli. To the regular motion of the priests' feet, Marduk seemed to stir on his litter and incline his head, as though nodding and smiling to the awestruck peasants standing deferentially along each side of the stone-paved track. In his right hand, Marduk held a wooden carving: a flowering branch of the traditional tree of life. His left hand was outstretched, reaching low, the fingers bent as though holding the hand of another. And indeed he was: only one person was allowed to hold the hand of this effigy of Marduk in public, and the watching peasants would perhaps have been all the more impressed by the figure who walked alongside the litter, reaching up and gripping Marduk's outstretched carved wooden hand. Resplendent in his ceremonial robes of purple, crimson and gold, this powerfully-built, hawk-nosed, black-bearded man was none other than the great king himself, Nebuchadnezzar II, fabled restorer of Babylon after its long centuries of neglect and decay. Babylon had been great before, in the era of the world-famous Hanging Gardens, but had long since suffered through destructive politics and warfare. Now, under Nebuchadnezzar's rule, it was restored to far more than even its former glory. The mighty Euphrates, as it rolled through the plain, had carved a niche for itself in the fertile soil, but annual flooding over thousands of years had raised its banks with layers of silt to create a series of natural levees throughout its course. Periodically these banks would burst here and there, allowing a fresh channel to leave the main stream, creating not a tributary but a branch, a minor arm of the great river itself. There were several such streams on the plain, and it was one of these secondary Euphrates rivers that approached the city of Babylon and washed its western walls. If the holy Euphrates represented the Holy Spirit, this branch of the river which approached Babylon served to illustrate the age-old saw: "Man does not approach spirit; spirit approaches man". After a while the procession would reach this smaller river at a point where the royal barge floated with furled sails, moored and ready, its scarlet-jacketed boatmen standing with their poles raised like guardsmen at attention. Across a broad gangway fashioned from pinewood brought from the distant Zagros mountains, the procession filed into the barge, settling Marduk's litter on a special dais amidships. With the crowd of onlookers following on the river bank, the gentle current would sweep the official party along, steadied by the boatmen's punting poles, the music of the choir and their accompaniment flushing startled ibises and herons from their cover among the willows and the reeds. The landing stage was close by the city walls, near the beautiful Gate of Ishtar. During the brief voyage, joined by some of the onlookers following along the river bank, the choral singers with their harps and lyres had kept up their hymn of praise to Marduk, and to the river which bore him along, interspersed with mythical sagas set to music. But now as the processional priests again raised their burden to disembark, taking up their solemn march with the rhythmically swaying idol, the drums and wind instruments blared out again, warning the waiting citizens that the most important ceremony of their year was under way, and the procession was about to enter the city streets. They were met at the gate and ushered into the city by the mayor of Babylon, resplendent in green and gold, accompanied by his council of elders. Their music echoed as they passed through the magnificent Gate of Ishtar, one of the dazzling wonders of the newly restored Babylon, its glazed tiles and bright mosaics ablaze with blue and green and gold— mythical figures of dragons and winged lions, eagle-headed gods, and lion-headed eagles; magical guardians of the city (we know what the gate looked like, because it has been painstakingly reconstructed for the Pergamon Museum in Berlin). The traditional paved route marking the sacred path of Marduk followed a circuitous course through the city streets. Now that the newly awakened soul had been symbolically introduced to the emotions—the heart—the procession wound its way close to the city walls watched by the townsfolk, silent and respectful. Eventually they reached the impressive temple of Marduk to await the next stage of this new year festival. The Arrogant, the Humble, and the WiseThe Babylonians were masters of the use of symbolism. The grand procession could take place only after a full week of preparatory ceremonies, the most important of which was the "humbling of the king": in front of the assembled council of priests and elders, the king's finery, robes and crown, were removed, and he was made to kneel before Marduk's image. At that moment, the great Nebuchadnezzar (as also his father Nabopolassar before him) would have seemed no better, no more important, than any of his subjects.The high priest then addressed the king in scathing and insulting tones, shouting unanswerable questions into his face. When he could give no answer, the priest would slap the king's face, pull his beard, twist his ears and tweak his nose until tears rolled down his cheeks. The point was being made that this person—though in fact the greatest king they had ever known, and probably genuinely respected at that—had, ritually at least, become a very ordinary creature, without pride or anger, without benefit of wealth or privilege. This symbolic shedding of worldly riches and respect was intended to convey the message that all traces of arrogance, of self-confidence even, must be made to yield to self-doubt, to a state of helplessness similar to that at birth, if not at death, in the face of the divine will. If there could be any meaningful preparation for the forthcoming meeting with spirit, this would have to be it—acquiring humility before your own soul. The ritual humiliation and temporary abandonment of power complete, the king would dress again in his robes and crown, before taking part in two sacrificial procedures outside the city gates. First, within a deep trench dug in the ground, he set fire to a bundle of reeds; then he was obliged to slaughter a white bull. Remember the spiritual hierarchy extending from the ground level of materiality, through the level of plants, through the level of animals, to the original high human level lost when the Garden of Eden was lost. The lower levels and the passions associated with them have to lose their power, their hold on the soul. This was the true "sacred path of Marduk". The following day another ritual was enacted: a special tabernacle was constructed, embroidered with golden thread. There the idol of Marduk was brought and set on a throne to await the visit of a subordinate but still very important god. In Babylonian mythology, this was one of his own sons: Nabo or Nebu, the god of learning and wisdom. As we already know, Nabo was the divine guardian of the neighbouring city of Borsippa on the banks of the mainstream Euphrates, and representative of the human intellect. Both Nebuchadnezzar and his father Nabopolassar had been named in his honour. When the tabernacle was ready, the image of Nabo was carried on his own cedar and rushwork litter borne by a retinue of his own priests, from his own temple in Borsippa, the ten miles or so to Babylon. The two idols were placed side by side beneath the golden surrounds of their tabernacle, in symbolic communication. All this took place before the public ceremonial began, and it is easy to see why. Wisdom, or the human mind, has to acknowledge and accept the supremacy or fatherhood of the soul before entering the spiritual path. The soul, represented of course by Marduk, would be first brought to life and then carried along by spirit. Inevitably, the awakened soul has to be brought to our awareness before reaching the Gate of Ishtar —the human heart, the seat of emotions personified by Venus or Ishtar. The existence of soul has to be accepted by the intellect, by the power of reason, before the inner journey becomes a meaningful reality. Then sooner or later, it must be accepted as the ruler by our own heart, our seat of value-judgment, and the means by which we can fully appreciate beauty and wonder.

Detail: Ishtar Gate—reconstructed entrance to the city of Babylon

Today as in ancient times, without the sacred river of spirit, the symbols of religion are fated to remain lifeless idols. Without spirit having quickened the soul, the ceremonies of religion are of no more value than the trappings of idols. Whilst the soul sleeps undisturbed and unsuspected, our images of heaven will have no more reality than those precious mosaics within the beautiful Gate of Ishtar.  |

Also by Ray DouglasThe Essence of the Upanishads |

Copyright© 2007, Undiscovered Worlds Press

|

|